Search Tactics: a specific action intended to get a particular result

While the above terms and actions get you to where you need to be to conduct a search, the tactics are used in the field for managing the details of your search.

Search by Vehicle

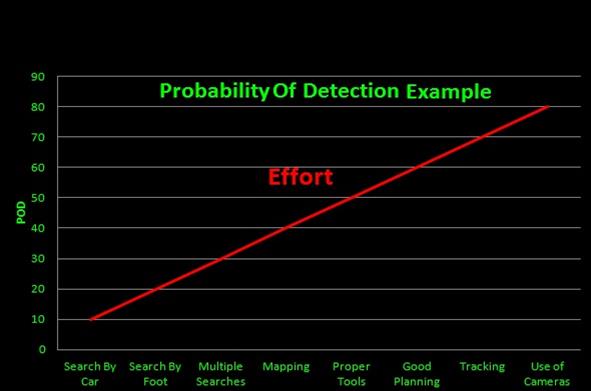

As previously noted, searching by vehicle has a very low POD, yet lots of ground can be covered in a short amount of time. Bring the proper tools in your go bag in the event you locate the missing pet. When searching by vehicle be sure there are no extraneous noises or distractions interfering with your senses. Turn off your AM/FM radio, do not bring young children along, and roll down your windows. Now is the time to look and listen for anything unusual. Be prepared to take swift action if the pet you are searching for suddenly appears.

Before starting out, have a plan of where you are going to search and review a map for anything unusual or areas where the missing pet may find of interest. Travel at a low rate of speed and always pull over for any vehicles that get stuck behind you. Make planned stops to get out of the vehicle at specific points of interest. Turn the engine off, get out of the vehicle, and just look and listen for a while. Makes notes for anything you've learned for future reference and planning. Upon your return, mark on your map where you had searched by vehicle.

Search by Foot

Being on foot is the most effective means to conduct a search for urban, rural and wilderness areas. Your go bag should be on your back at all times, properly equipped.

While moving, you must be quiet, no calling or whistling for the missing pet. Making any noise, even your footsteps, may be enough to scare away the pet long before you get close to it. Calling out loud for the pet will most certainly scare it off before you even get a chance to see it. Many searches are unsuccessful because of well intended people searching on foot yelling out a pets name only to scare it further and further away from its domain creating a forever lost scenario.

When you get to a point of interest, and/or after about ten minutes of moving, come to a stop. Look all around and listen (yes, even in noisy urban areas too). Look for any movement, tracks or signs of the missing pet. If you're in a rural or wilderness area, or in a quiet urban area, softly call out to the pet without using its name (using the pets name in an unfamiliar area often has adverse effects as it confuses it). Dogs and cats have exceptional hearing, they can hear ten times further than humans. There is never a time to yell or be loud. The point of calling out softly is an attempt to create movement by the pet that you can either see or hear, as it might be in your immediate vicinity.

Always maintain awareness of your surroundings, both for safety and navigation. In an urban area, navigation will be much easier but you need to be careful about autos, bikes and other traffic hazards. In rural and wilderness areas you need to use caution for terrain hazards and you should always know which direction you are traveling. Civilizations many years ago, and some still to this day, would use N,S,E or W as their only means of direction. For example, instead of saying "go up the trail one mile and turn left", they would say "go north on the trail one mile and turn west". The use of left or right was not part of their language and they always had a heightened sense of their location, and as a result, their senses were heightened when they traveled. So when you're searching on foot, use N, S, E, or W as your primary means of navigation and how you communicate your travels to others.

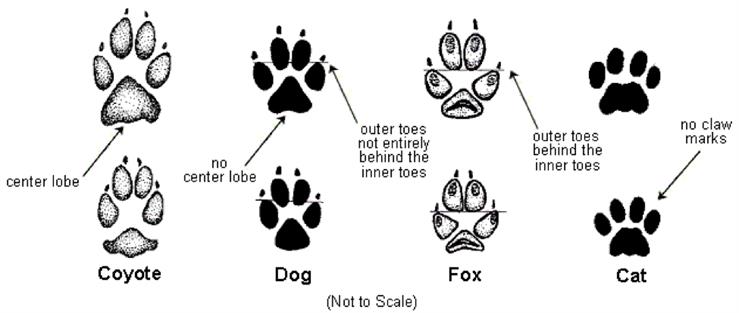

Should you find tracks, be sure to take multiple photos from varying angles (best to have a track between you and the sun for optimum contrast). After taking photos and making a note of the specific location, clear the tracks from the ground (by hand, foot, rake, or whatever). This is essentially creating a track trap, so upon your return you can tell if fresh tracks appear or not. If you have a good sense that the tracks are from the missing pet, this would make a good placement for a trail camera.

Continue searching your planned area. Think as the missing pet might in the given surroundings. Dogs especially will take the path of least resistance and prefer to travel downhill instead of uphill if they have a choice. Dogs will generally go around minimal interferences, like an old broken fence, while cats may simply climb up and over it. Think like a dog, be like a cat.

If the pets PLS was near an urban street or a rural highway, then those areas need to be searched. The objective is to determine if the pet was injured or deceased as a consequence from being near vehicle traffic. This needs to be done to eliminate the possibility. For example, if there is a rural highway adjoining the pet owners home, the highway shoulder on both sides of the highway must be searched for at least one-half mile either side of the home.

The Power of Observation

Our daily life rarely demands our brain to provide the power of observation for which it is capable. There are specific techniques you can use in the field to increase your power of observation (examples presume rural or wilderness areas but similar examples can be made for urban areas).

Scanned Observations

1. Stop, then observe.

Of course a search on foot will require you to be walking most of the time, but your power of observation is increased when you stop to observe.

2. Scan slowly

Make a conscious effort to slowly scan the environment, this will create focus and attention. Start by observing "Short Range", from left to right and back again. Next observe "Mid Range", again from left to right and back again. Continue on with "Long Range" and "Very Long Range".

Example Possible Observations:

Short Range (0 to 20 yards) - tracks, fur, feces, urine, food, injured pet, hiding pet, signs of pets passage (broken plants), pets belongings (collar, tags), pathways.

Mid Range (20 to 50 yards) - missing pet, other animals, people, animal or people paths into and out of area, birds or other wildlife indicating presence of lost pet.

Long Range (50 to 100 yards) - missing pet movement or placement, wildlife movement, wind direction, people, extended pathways

Very Long Range (100 yards and beyond) - pet or animal movement against sunrise or sunset, possible areas of interest to check, incoming weather, distant pathways

Range Chart For Unaided Observations (compare to lost pet for scale):

100 Yards - An single person or large dog can be seen

300 Yards - Outline of people can be seen, no distinguishing features

540 Yards - People appear as a vague shape, larger animals can be recognized, like a cow, but not smaller ones.

1000 Yards - People very difficult to make out

2000 Yards - People or animals cannot be seen

Think Critically

The quality of your observation will improve by skillfully analyzing and assessing what you see.

Make Notes

Note taking is a proven means to increase your power of observation because your brain will process the observation first through the sight, and again by writing it down.

Inattentional Blindness (the failure to notice a fully visible but unexpected object because attention was engaged on another task, event, or object. [Mack, 1998])

Avoid the phenomenon of inattentional blindness by being aware of its existence and remaining focused on the search at hand by minimizing distractions. This well documented phenomenon would cause you to blindly walk directly past a lost pet and you would never see it because your brain is too busy processing other information.

Ten In / Ten Out (written and attributed to Craig Bannerman, fire fighter and SAR member from the Black Mountain Fire Department in North Carolina)

This behavior is directly related to human Search and Rescue efforts but can equally be applied to pet searches.

"More clues are missed in the first ten minutes and last ten minutes of a search than at any other time . Before you start the mission be in "search mode". That means the pack is adjusted, the mission is known, your shoes are tied and you have cleaned your glasses. When the first step is made on the mission the scanning for clues should start. The last ten minutes are when are the "horse to the barn syndrome" kicks in. That's when searchers are ready to climb in the truck, eat and be back at the CP. We tend to rush and to develop tunnel vision on the pick-up point. As a result we miss clues. The focus must remain on the subject until the mission is over and the debriefing is done."

Night Observations

Use the weather and moonlight to your advantage when possible. Allow ample time for your eyes to adjust to the dark before proceeding.

When going from a dark area to a lighted area (or a flashlight off, flashlight on, flashlight off) condition, close one eye and don't open it until you are back in the dark. This will retain your night vision in the eye that was closed.

As darkness approaches things that are yellow or red lose their brightness and greens and blues in the landscape appear much more bright relative to their surroundings [Purkinje Effect].

Most animals have a reflective layer in their eyes which help them see at night (tapetum lucidum). When light hits this reflective layer it will produce a color, which most commonly are:

Dogs - Most are green

Cats - Bright green (Siamese cats are red)

Horses - Blue

Fox - White or pale blue

Coyote - Yellowish/Green

Possum - Red

Never point a flashlight directly at a fellow searcher. Always carry a small light in a pocket which has multiple lens colors (red/blue/white) with very low illumination for checking equipment, taking notes, etc., so that your night vision isn't impaired and it won't scare off nearby animals.

A Dogs Vision Compared to Ours

A dogs vision is different than a humans ability to see. Dogs have a significant advantage to detect motion compared to humans. When a dog recognizes a human, it is most likely due to familiar movements rather than facial recognition. A dogs field of view is wider than ours (250 vs. 190 degrees wide) because their eyes are placed more along the side of the head. However, the dogs ability to focus on distant objects is about half that of ours due to the separation of their eyes. Dogs can see in the dark much better than us, by about five times. Dogs are not color blind as often thought, but their view of color is muted compared to ours. Among various colors, they distinguish best between yellow and blue and are mostly color blind to red and green. Also, a dogs ability to discern objects at a given distance is less than ours. For example, something we could see sharply at eighty feet away, the dog must be twenty feet away for the same level of clarity.

Why is a dogs vision important when searching and using our powers of observation? As you may have already deduced, the dog is much more likely to detect you before you see it (even putting aside their primary senses of smell and hearing). And if you do observe the dog and can get relatively close to it, you will have a better understanding of the dogs ability to observe you and your behavior. Do you appear jittery or perhaps acting as a predator might? Or are you relaxed, approaching with a sense of calmness the dog detects because of your lack of awkward motions. Even if you are the dogs owner, being out of place (not home) will cause you to react differently which the dog detects as a threat rather than a companion. Tread lightly and speak softly when you and the dog are within visual distance of one another.